In a city with a growing black population, only two blacks have served on the City Council, each for just one term. The School Board has been more diverse.

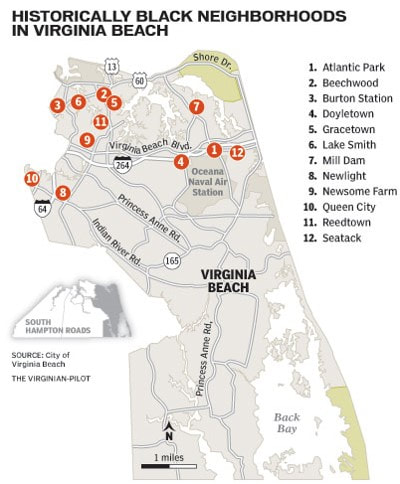

In one of the city's oldest black neighborhoods, residents still lack city sewer and water service. And 20 years after Greekfest, the city's leaders and residents still wrestle with the legacy of the civil unrest and police crackdown during the gathering of black fraternities and sororities. The 1989 event brought the city national attention and left some with the impression that Virginia Beach's crown jewel - its Oceanfront - didn't welcome blacks. Ron Villanueva, the first Filipino American elected to the City Council, points to more racial inclusiveness in the city's hiring practices and awarding of contracts in recent years. The city's mayor, Will Sessoms, calls the Beach's diversity "great." "Everybody gets along fine," he says. "A vast majority of people don't see color." When it comes to blacks holding positions of power, though, Virginia Beach trails all other South Hampton Roads cities, which have elected or hired more blacks to lead as mayors, council members, city managers and state delegates. "There are some racial problems that are challenging that need to be overcome," said Georgia Allen, president of the city's NAACP chapter. She grew up in Virginia Beach when the Oceanfront was segregated. "Are we moving forward? Yes. Are we taking baby steps or taking giant steps? I would say baby steps." Burton Station is a stark reminder of the lack of political clout, history of disenfranchisement and corrosion of public trust facing blacks. In this neighborhood built by freed slaves, off busy Northampton Boulevard near the Norfolk city line, generations of blacks have waited for basic water and sewer service. Fewer than 20 families remain in what used to be a community of 100 families. Some left when their homes fell into disrepair, and the city, wanting the land for industrial uses, wouldn't allow them to make improvements. Others sold their land to Virginia Beach or Norfolk. Naomi Morgan remains. This is where she raised her three children. This is where her husband died. If she sells her 1.5 -acre plot, she wants a fair price, and she said she hasn't received one yet. For more than a week this summer, Morgan, 66, had to walk up Burton Station Road to her neighbor's house to ferry jugs of water. She couldn't flush her toilets or wash her pots and pans. Her water pump had broken, and her usual plumber was unavailable. "When I had to do that, I used to think of people in Africa that have to carry their water," she said. She looks at the neighborhoods around her and sees thriving communities with access to city services. "I call that discrimination," Morgan said. "Everybody has got water and sewer but us." After several failed discussions over the decades about services and development, city leaders and Burton Station property owners met again this year. The City Council dedicated $4.8 million in this year's budget to install street lights and lay the water and sewer lines. The work is expected to start by late 2010. "It's moving, which is great," said Warren Harris, the city's director of economic development. "It's been a lot of start and stops and some expectations that weren't delivered and weren't met." Morgan says there has been an improvement in the relationship between the city and the black property owners over the past year. Trust, however, is elusive, she said. Morgan went to segregated schools. Her husband was killed in their yard by a white police officer in 1975, an incident police ruled self-defense. The shooting sparked violence in the neighborhood, and some questioned whether the shooting was racially motivated. Three years after the shooting, a judge dismissed a civil suit filed by Morgan against the officer involved. In 1962, Princess Anne County's Board of Supervisors rezoned much of Burton Station's land for industrial uses without notifying the residents. It took 20 years for the city to restore the residential zoning. Then in the 1990s, the city of Virginia Beach tried to establish a housing and redevelopment authority with the power to take property such as Burton Station using eminent domain. All the while, residents begged for city services. Beach officials declined to extend water and sewer services to prevent more homes from being built. City officials instead used federal money to move residents out of the community, which was near the Norfolk International Airport crash zone. Then, as many moved away, the cost of extending water and sewer for those who remained was deemed too costly, said Andrew Friedman, the city's director of housing and neighborhood preservation. Even now, with money in the budget and plans on the books, Burton Station property owners are wary. "People have been hurt so much here," Morgan said. To understand the roots of mistrust, black leaders say you have to understand Virginia Beach history, which is peppered with stories of racism and inequality. When Virginia Beach incorporated in the early 1900s, its boundaries skirted the heavily black community of Seatack. Even now, few blacks live in the original resort strip. In the 2000 U.S. census, 5.4 percent of the resort area's population was black. For the first half of the 20th century, blacks cleaned the segregated town's hotels but couldn't go onto the beach. Sadie Shaw, 90, lived about a mile from the Oceanfront in Seatack but couldn't stroll onto the beach until the early 1960s, when the area integrated. Shaw had to travel almost 10 miles to the beaches along Shore Drive. "We couldn't go on the sand, unless I was taking care of a white child," Shaw said. The city's blacks were concentrated in a few communities, such as Seatack, Gracetown, Newsome Farm and Burton Station. These neighborhoods were scattered throughout the northern part of the city and were self-sufficient, with their own stores and churches. In 1963, the city of Virginia Beach merged with Princess Anne County and quickly grew into a sprawling suburb. In the 1960s, the population more than doubled, to 172,106 residents. Of the new arrivals, 95 percent were white. Norfolk and Portsmouth saw their white populations decline during the same time. Whites weren't alone in retreating to Virginia Beach. Professional blacks - teachers, lawyers, doctors - from neighboring cities also came looking for their share of the suburban dream. L&J Gardens, off North ampton Boulevard near Burton Station, was built for them. "It was the lifestyle, the quality of housing, and that the houses were not that crowded " that drew Helen Shropshire and her husband to Virginia Beach from Portsmouth in 1964. "We have loved it here," said Shropshire, a retired school principal. The landscape of Virginia Beach was changing. Developers were building homes and neighborhoods in Virginia Beach at a ferocious speed. In the 1970s, Virginia Beach's black residents started pushing the city to provide their communities with water and sewer and to pave their gravel streets. The neighborhoods had not kept up with the new, mostly white, subdivisions. It took the city until 1998 to finish $59 million in improvements. The federal government had to step in twice to ensure that money was being spent appropriately and quickly, fostering resentment among some black residents. As each neighborhood modernized, white residents moved in. In some cases, the signs that it had been a historically black neighborhood all but disappeared. Prescott Sherrod, the owner of a technology firm and a member of the city's development authority, said he has been asked by folks new to Virginia Beach, "Where do the minorities live?" "It's not a question here," Sherrod said about the city. "They live everywhere. You can live where you want, and most importantly where you can afford to live." Yet, in the 1980s, as Virginia Beach's population continued to multiply, there was a sense from some blacks that it really wasn't for them, said Sandra Smith-Jones, a current Beach School Board member who moved here then. It wasn't anything obvious. People would say that getting a job with the city or school division was hard if you were black, Smith-Jones said. At that time, more than 60 percent of minorities working for the city held maintenance jobs. During her first few years in the area, Smith-Jones said she didn't visit the beach. "There are places where you're not welcomed, where you're not supposed to be," said Smith-Jones, who had moved to Virginia from Long Island. Then, in 1989, Greekfest happened. Thousands of students from black fraternities and sororities arrived in Virginia Beach for their annual gathering. A group of rowdy young people at the Oceanfront, a lack of planning by the city and poor crowd control by police led to the most serious racial conflict in the city's history. Smith-Jones had planned to organize a forum on Greekfest before the anniversary to help the community reconcile. She is still committed to the idea, she said, but it will likely happen later. After Greekfest, the city formed several community groups that focused on its minority population and race relations. The Human Rights Commission was created to review civil rights complaints, but it has no investigative power and over the years has morphed into a forum to discuss such issues as youth violence, minority recruitment in the police and fire departments, and ways to reduce crime in neighborhoods. The Minority Business Council, established in 1995, was aimed at increasing the number of contracts going to companies owned by minorities and women. In the past few years, the city has seen an increase in the proportion of money spent with minority firms for city work, to 5.4 percent from 1.8 percent in 2004. That's still short of the city's 10 percent goal. Only a quarter of the money in 2008, $3 million of the $12.2 million, was spent on the big construction projects. "You're not seeing movement where the real money is," said Louisa Strayhorn, one of the two blacks elected to the City Council. Strayhorn helped establish the city's Minority Business Council. She said she would like to see the city be more aggressive about doing business with minority companies. The proportion of black residents in Virginia Beach also increased from 14 percent in 1990 to 19 percent in 2000, the most recent U.S. census, or from 54,671 to 80,593. Even with that increase, it is still the whitest city in South Hampton Roads. Smaller suburban Chesapeake, by comparison, was 29 percent black and 67 percent white in 2000. As the city's minority population grew, the NAACP and some residents urged the City Council to redraw its election districts to create a more heavily minority voting ward, or at least alter the way candidates are elected. While seven of the 11 council members represent districts, they must win the citywide vote, too. The other three council members and mayor are elected at-large. Unlike Virginia Beach's hybrid system, Chesapeake, Norfolk, Suffolk and Portsmouth elect council members either by ward or at-large. Portsmouth, Chesapeake and Suffolk have each had black mayors. Virginia Beach's blended neighborhoods make it difficult to draw majority-minority districts, and council members defend the voting system, arguing that elected officials represent the entire city and not just their district. Still, the issue continues to come up, most recently in forums before last year's election. "If you want to have some proportionate representation, you would think there would be some African Americans on City Council," said Sherrod, a local businessman. While he is the lone minority on the 11-member City Council, Villanueva said progress can be measured by the increasing number of blacks who are running for public office. Last year, seven black candidates ran for the City Council and School Board. One, incumbent Smith-Jones, won. Recruiting viable black candidates to run is a challenge, especially when they see how their peers are treated, Strayhorn said. When she ran for re-election in 1998, she said her campaign workers received racist threats. More recently, police Capt. John Bell Jr., who is black, was encouraged to run for the sheriff's office as a Democrat. But when long time Republican state Sen. Ken Stolle announced that he planned to run, many of Bell's initial supporters abandoned him, Strayhorn said. It confirmed to many in the black community that local leaders would continue to rally around the status quo, Strayhorn said. Allen, the head of the NAACP in Virginia Beach, gives the city credit for some hiring improvements. The Convention and Visitor s Bureau hired someone specifically to attract black-focused events to the city. Two blacks and a Filipino have been hired since 2007 to lead high-profile departments - Economic Development and Public Works as well as the Office of the City Auditor. Still, the city's top leadership continues to be substantially white. In 1988, six of the more than 90 administrators were minority. Twenty years later, there were eight minorities among the same number of total administrators. Few vacancies exist among the top ranks and very rarely are new people hired, said Gayle S. Koscho, the city's diversity and special programs manager. "There's still room to grow," Koscho said. "There's no question." More significant strides have been made among the city's degreed work force, such as engineers, planners and financial analysts. In 1988, 9 percent of the city's professionals were minority; last year it was 29 percent. The city's fire, police and sheriff's departments have also increased their proportion of minorities, from 11 percent in 1988 to 19 percent last year. Still, problems persist. In 2006, the U.S. Justice Department determined that the math portion of the police entrance exams discriminated against black and Hispanic applicants. The city agreed to change how it scored the exams and set up a fund to compensate applicants. Chesapeake's and Portsmouth's fire and police departments also came under similar scrutiny over discriminatory hiring in recent years and have been forced to change the exams. Minorities in total make up 18 percent of the 806 sworn officers in the Police Department this year. But only 10 percent of officers are black in a city where 19 percent of the residents are black, according to the most recent census, in 2000. Officer Enrique Taitt, the Police Department's recruiter, said getting blacks to join the force is a challenge. Many would prefer to work with the Federal Bureau of Investigation instead and there's still tension between the black community and the police in general, Taitt said. Without blacks in positions of power to fight for racial equity, change has occurred too slowly on issues from minority contracting to improving neighborhoods, Strayhorn said. "If you're not there pushing it, it's not going to be a priority for them," she said. "Does it mean that they hate you, or are going to work against you? No. It's not a priority." Deirdre Fernandes, (757) 222-5121, [email protected] Click here for original article.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Virginia African American Cultural Center

Join our mailing list |

Share your thoughts!Administrative Office:

4532 Bonney Rd. Ste D Virginia Beach, VA 23462 Telephone : 757-707-8478 Email : [email protected] |

© Virginia African American Cultural Center, Inc. All rights reserved.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed